Somewhere in the South Jamaica neighborhood of Queens, New York, sits a peculiar house ornate with detailed mosaics and mirrors. In its basement, unbeknownst to passersby, lies an equally uncommon room, filled with percussion instruments, African artifacts, rugs, computer screens, medical equipment and a hand-painted drum set. The man who has occupied these premises for close to fifty years is drum master Milford Graves, the subject of Jake Meginsky and Neil Young’s new documentary.

Graves started to make his mark on the international jazz scene in the mid-sixties, through his drumming with figures of the avant-garde movement such as Giuseppi Logan, Albert Ayler, the New York Art Quartet, as well as through his own leader work. The Queens native was then among a handful of musicians who pioneered a non-metronomic approach to pulsation. But this is not what Full Mantis is primarily about. Stemming from Meginsky’s fifteen-years student-master relationship with Graves, the film grew out of the director’s documentation of the musician’s teachings, first in audio form and later equipped with a camera.

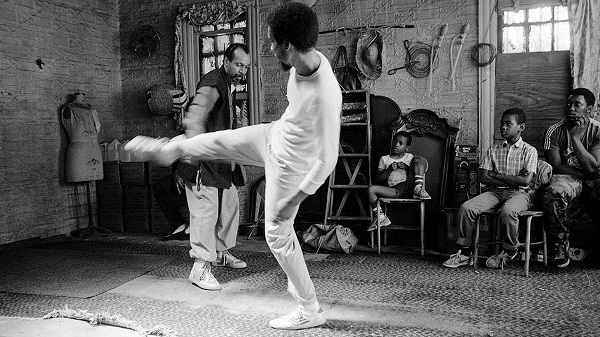

Since the heavy days of the sixties, Graves has been exploring a number of avenues well outside of traditional musician side-projects. He created Yara, his own Yoruba-named martial art, undertook research on the human heart and its rhythms, developed an herbalist and acupuncturist practice. Those diverse yet interconnected topics make up the foundation of Graves’ teachings.

His underground laboratory and adjacent luxuriant garden constitute the set of Full Mantis. In good part, this is a film of silent details, accumulated and carefully laid-out traces of a multidimensional life. Accordingly, the film contains many beautifully shot close-ups, glimpses of stories untold. On a shelf, a copy of Prussian scientist Hermann von Helmholtz’s On the Sensations of Tone --- a text important to the sixties jazz avant-garde ---, a 1966 hand-painted record issued by Graves and pianist Don Pullen via their "Self-Reliance Program," a forebearer in the movement for musical autonomy soon to bloom.

The framework of this confined setting is blown open by the use of archival footage documenting Graves’ presence on the world stage. Part of this material will be familiar to those already well acquainted with the musician’s work, but is put to effective use. Long excerpts of a 1973 concert in Belgium featuring Graves’ radical formation of drums and three horns, Graves playing percussion during a party in rural Japan, a striking sequence showing the drummer with butoh dancer and improvisor Min Tanaka.

Private photographic archives provide the basis from which one of the most remarkable sequences is built. Black and white pictures of Yara training, impressively edited together. A flyer for a 1969 event featuring the martial art --- "the black way of self-protection" --- alongside the Last Poets and poetry readings by Askia M. Touré and Marvin X gives another hint of an untold story, taking place in the era of Black Power.

The music heard throughout the film is centered mainly on Graves’ solo work on his snare-less drum kit, most often accompanied by his vocalizations. It draws heavily on career-spanning commercially available recordings. Often, a layer of undulating gong resonances hypnotically sits under Graves’ voice in spoken word sequences. Interestingly, the film debuts a so far unknown electronic facet of Graves’ music, consisting of algorithmically transformed heartbeat recordings sounding eerily compatible with free jazz soloing.

The oral nature of Graves’ philosophy deeply impacts the film. One of its marking traits is that it does not attempt to normalize Graves’ work. The musician, and he alone, probes at length territories that will be unfamiliar to most viewers, in sequences that other filmmakers would likely have edited down and balanced with talking heads bringing outside validation. The grainy, hand-held footage of Graves and Tanaka takes place in a gym, the two artists surrounded by autistic children sitting on the floor. Progressively, more and more children get up and join Tanaka, dancing. A small child stands inches away from Graves’ kit, seemingly mesmerized. Perhaps this sequence could be considered as central, plainly demonstrating that however idiosyncratic, Graves’ theories simply work.

The fact that films tend to become the de facto entry points into their subjects’ work --- is it the irreducible density of information moving images appear to carry ? --- seems not to have preoccupied the directors, who have not created a general introduction to Graves. This approach is a welcome one, as it acknowledges the existence of a good amount of print material that a film doesn’t have to supersede.*

Full Mantis is one film about Milford Graves out of several that could be made. Lower profile features** --- excerpted here --- have already been produced, and at least one other film, by William DuVall, has been in preparation. Meginsky and Young’s picture might not be the film jazz history devotees would want to see, but it is certainly in accordance with Graves’ eschewing of labels. A good deal of Graves’ multidimensional work is about organic relationships between the body, its environment, sound, music. Full Mantis is a personal take on a singular man, a take that unfolds as the organic outgrowth of a long-lasting relationship, in the process delivering fragments of an individual truth.